Modern vulnerability resolution (Cross-Site Scripting). Validation vs. Encoding

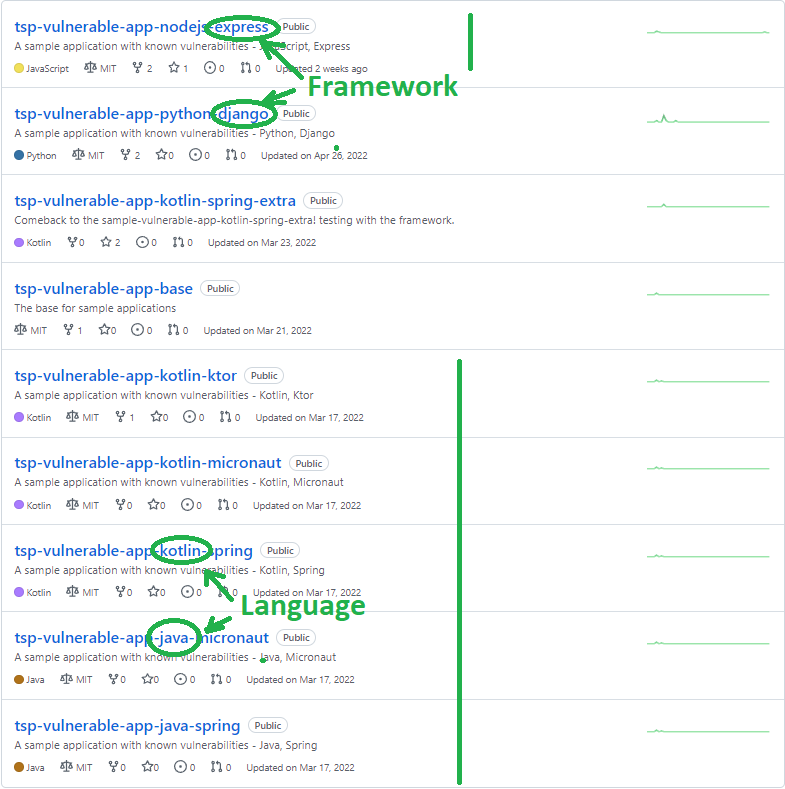

Let’s look at the most basic Cross-Site Scripting example (XSS). We’ll use examples in a couple of different popular programming languages and frameworks for that.

A basic reflected Cross-Site Scripting injection example:

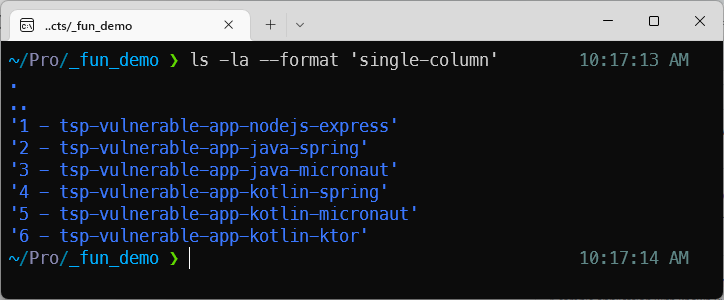

We will take the most basic example in a couple of programming languages and frameworks from here: https://github.com/samoylenko?tab=repositories&q=vulnerable-app

We clone the repositories to run our experiment:

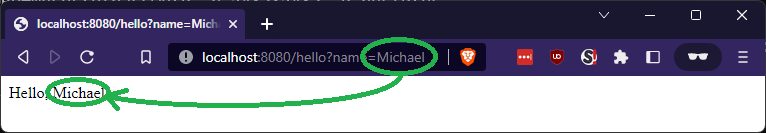

All these applications have a /hello endpoint that will respond Hello, $name to a parameter in the URL.

For example,

http://localhost:8080/hello?name=Michael will return Hello, Michael

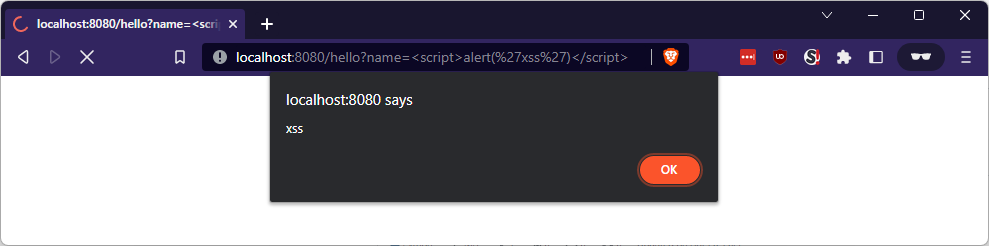

So what happens when we try to inject the classic <script>alert('xss')</script> in that parameter?

Let’s find out!

NodeJS - Express Application

| Language | Framework |

|---|---|

JavaScript (Node) |

Express |

The first example in NodeJS is obvious enough:

app.get('/hello', function (req, res) {

res.send(`Hello, ${req.query.name}`)

})As expected, we got an XSS:

No surprise here.

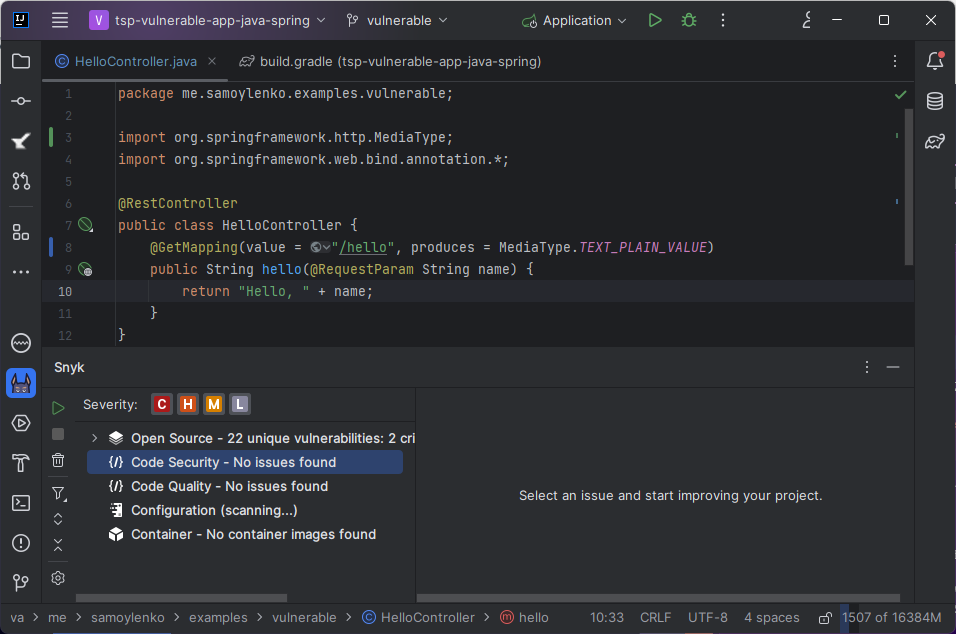

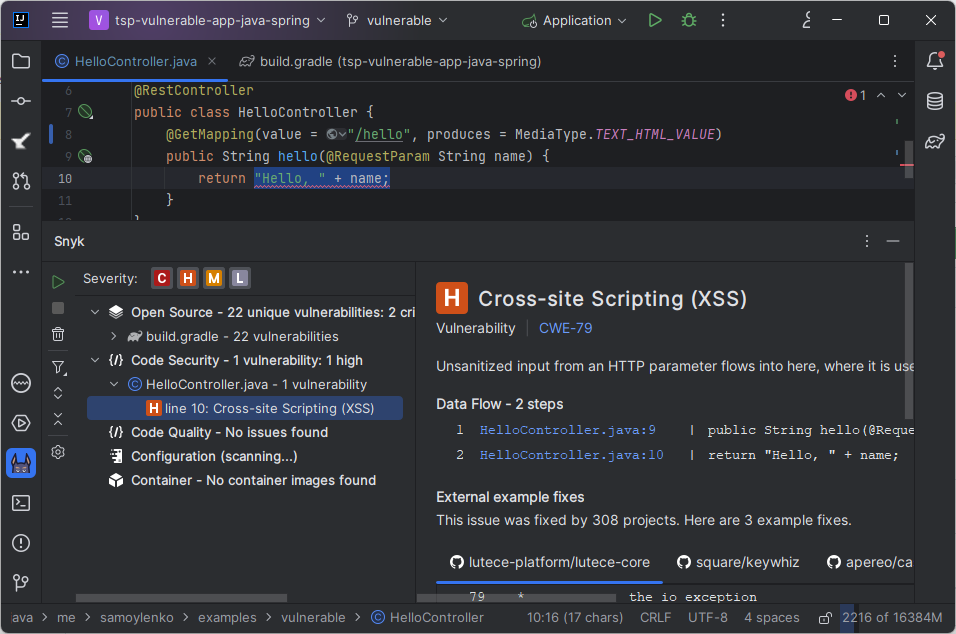

Java - Spring Application

| Language | Framework |

|---|---|

Java |

Spring |

Looks pretty much the same, right? Classic:

@RestController

public class HelloController {

@GetMapping("/hello")

public String hello(@RequestParam String name) {

return "Hello, " + name;

}

}Of course, there’s an XSS if we run that!

Java - Micronaut Application

| Language | Framework |

|---|---|

Java |

Micronaut |

Same code, right? Would you expect a different result with this code? Only code annotations differ because the framework is different:

@Controller("/hello")

class HelloController {

@Get

String getName(@QueryValue String name) {

return "Hello, " + name;

}

}Let’s try it:

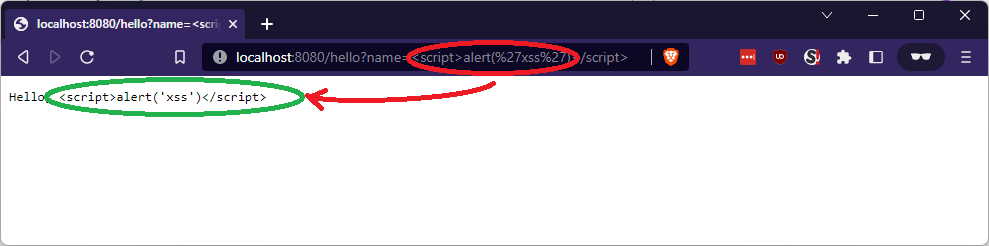

Wait, what? No XSS! The injected code was escaped? Or validated? Was it? But how? It’s literally the same code as the previous example!

Let’s finish our experiment before we investigate what is really going on

| I’ve also been planning to extend this article with deserialization vulnerabilities for a while - all out of my love for Kotlin. I never got back to it, but the table below also contains Kotlin apps. |

| Language | Framework | Did we get the XSS as expected with the same operation (add user input to output as is)? |

|---|---|---|

NodeJS |

Express |

Yes |

Java |

Spring |

Yes |

Java |

Micronaut |

No! |

Kotlin |

Spring |

Yes |

Kotlin |

Micronaut |

No! |

Kotlin |

Ktor |

No! |

Let’s investigate

So what is going on? Does the string get encoded in HTML? Is it escaped? Is there an input validation?

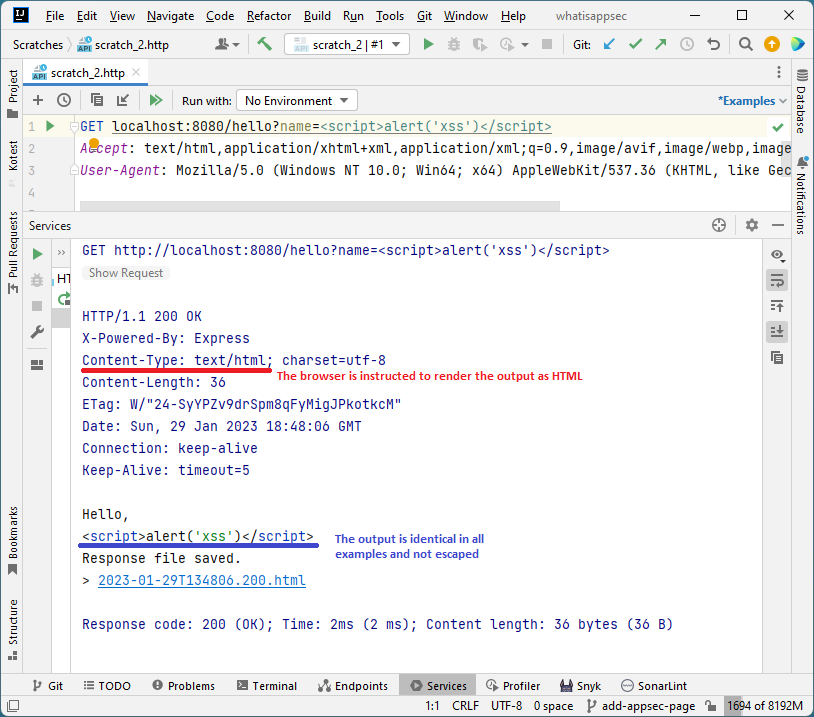

Let’s take a look at the HTTP protocol-level information. In each of the following three request pairs:

-

The first request emulates a browser and instructs the server on the type of content it accepts (HTML)

-

The second request is a plain

GETrequest (no headers) - to see how that affects the server setting theContent-Typeserver in the response.

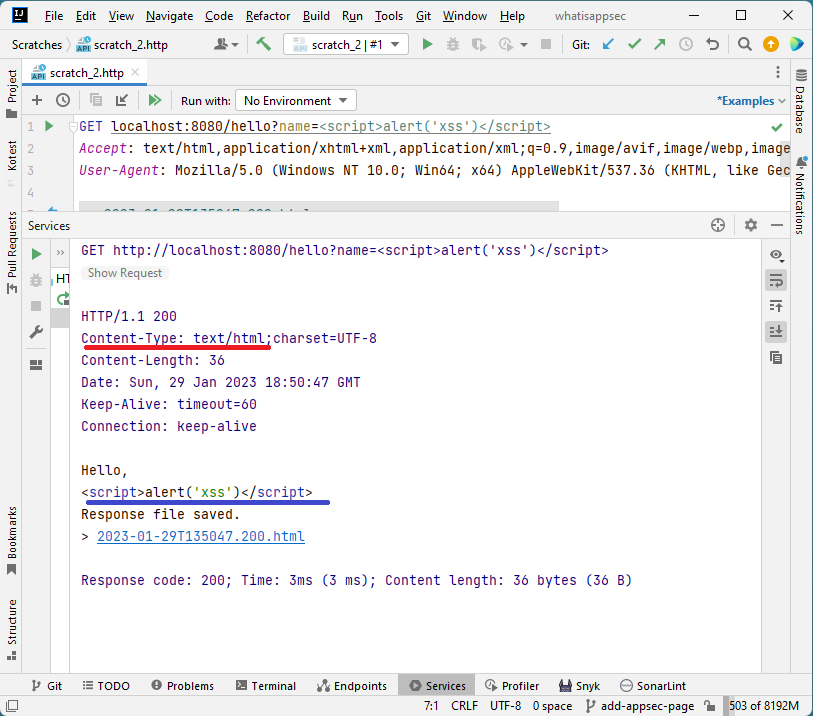

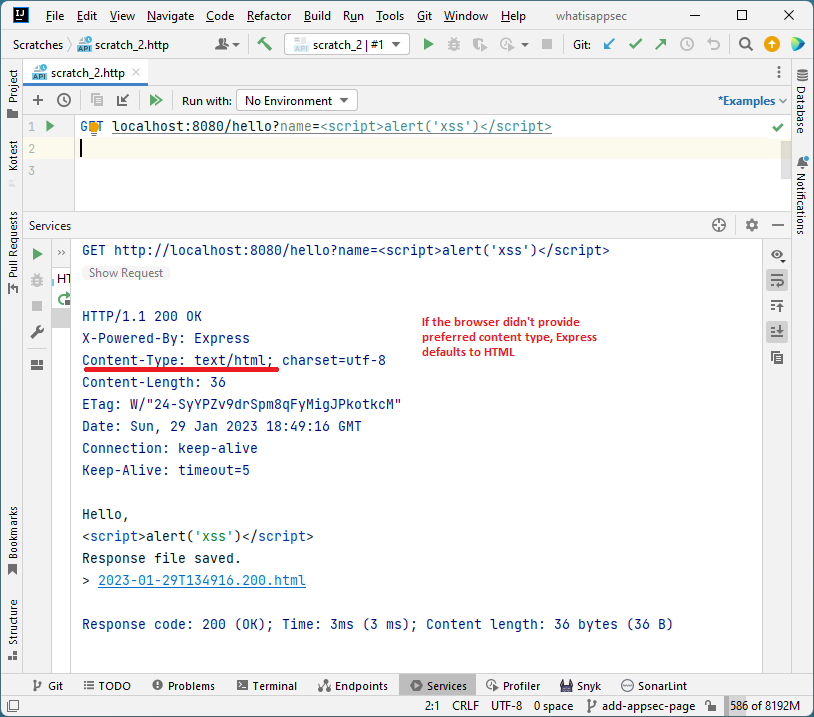

NodeJS + Express (default request headers)

NodeJS + Express (no extra headers)

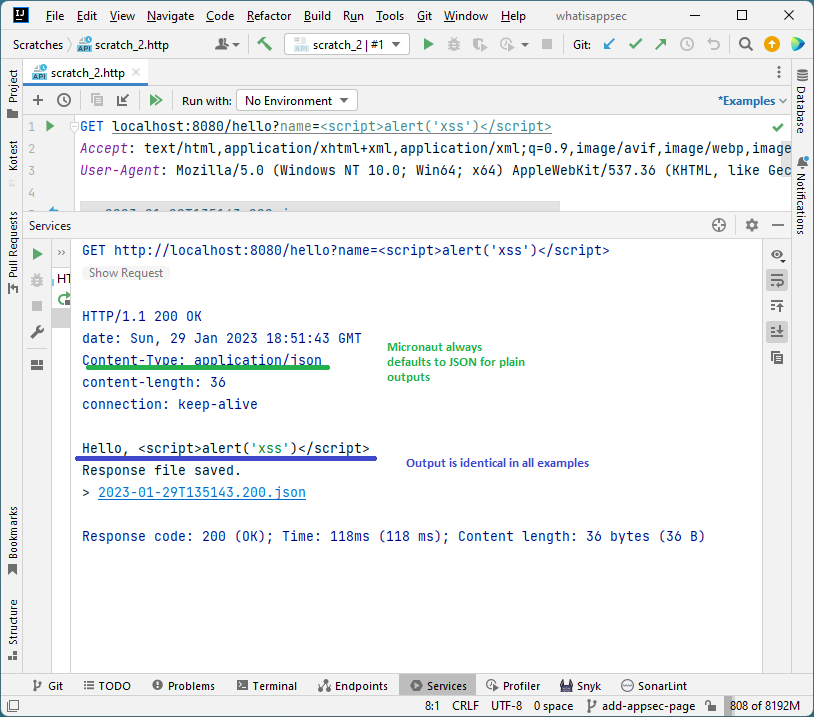

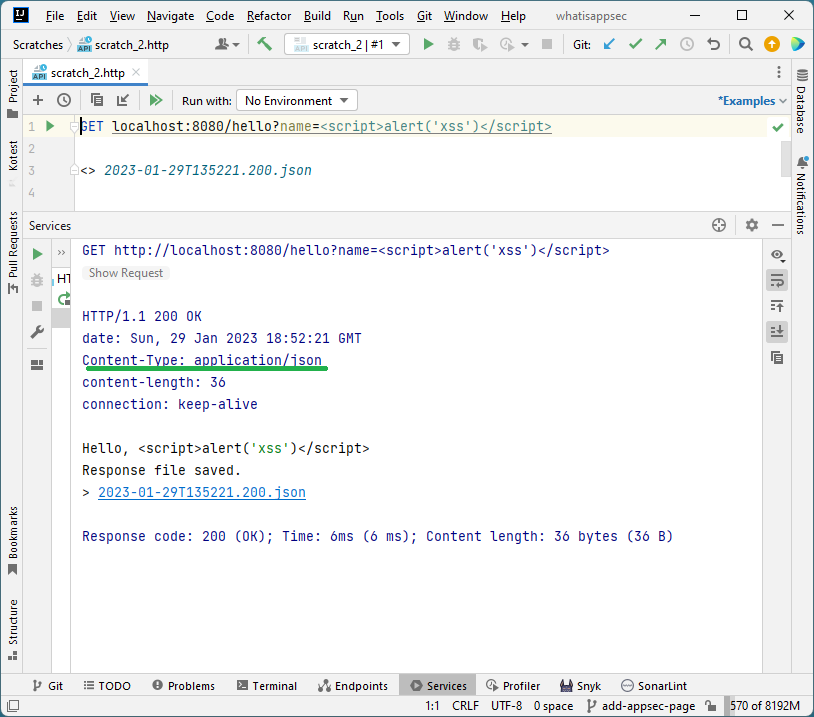

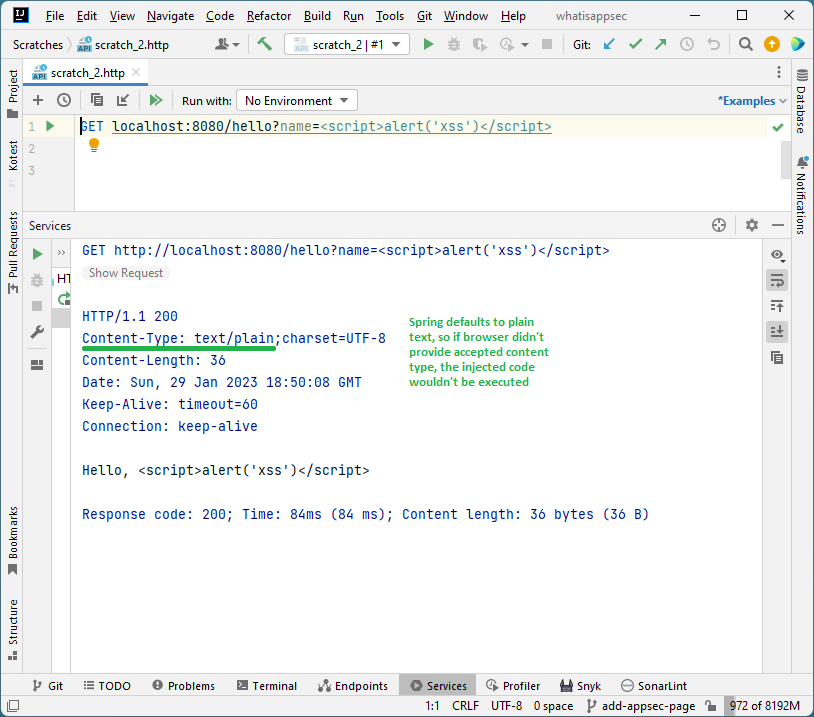

Java + Spring (no extra headers)

So what do we get?

We got the following:

-

The output (the

Hello, <script>alert('xss')</script>string) is identical in all cases. And even though nothing is being sanitized or validated, it doesn’t execute when using the Micronaut framework. -

The only difference between having XSS and not is the

Content-Typeheader instructing the browser on treating the server output. -

The Cross-Site Scripting vulnerability was prevented by the framework not trying to satisfy the browser’s

Acceptheader and setting theContent-Typeheader explicitly depending on the content it produced.

What is the proper fix for this vulnerability?

Well, that depends on how you define the security of your application. Many people will say that just the fact that the output is encoded correctly (plaintext or JSON, not HTML, that would execute the script) is described as a proper solution in the Application Security Verfication Standard (ASVS).

But most still view it as just the fact that the code doesn’t execute is insufficient and malicious input must be prevented. It may not come as HTML today, but a future change in code or browsers may someday make it executable for any reason. It’s not secure to rely just on the header and hope that behavior never changes.

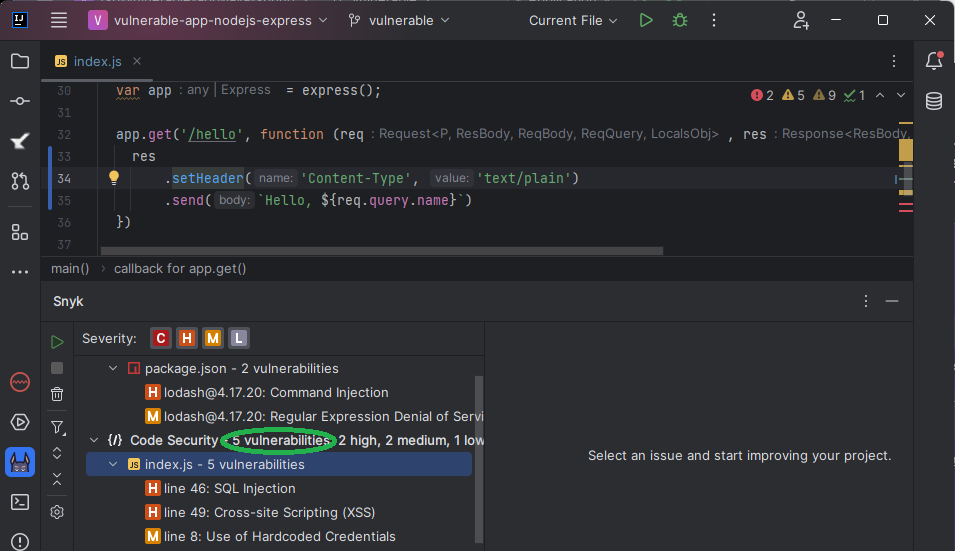

What do static analysis tools (SAST) say?

Most static security scanners (SAST) indeed don’t check the Content-Type header and would always highlight it as a finding.

But since most of them are now suggesting a fix through AI, they sometimes offer a solution doing precisely that - explicitly setting the Content-Type header to something other than text/html.

I rely on my favorite scanner, Snyk, which knows the scenario described here well.

Conclusion

Based on what we just learned, I will try to carefully make the following statements:

-

In the modern web, the server and browser work together to protect the user.

-

There may be much better ways to fix injection-type vulnerabilities than implement a custom, often regex-based filtering or escaping functions in code. Even OWASP Application Security Verification Project (ASVS, probably the best source of information on preventing application security issues) supports that:

With modern web application architecture, output encoding is more important than ever. It is difficult to provide robust input validation in certain scenarios, so the use of safer API such as parameterized queries, auto-escaping templating frameworks, or carefully chosen output encoding is critical to the security of the application.

— Application Security Verification Standard

V5 Validation,Sanitization and Encoding -

Most modern frameworks and libraries already contain most, if not all, the required functionality to do that already, so there’s often no need to write any extra code or make the code more complex trying to fix security issues. All it usually takes is to read the framework/library documentation carefully.

-

Constructing a raw HTML output in code no longer makes sense - templates and front-end frameworks exist for that.

-

Using a modern framework or a well-known library alone in the first place makes it hard to create a new vulnerability.

-

-

Regardless if you see the

Content-Typeheader fix discussed in this article as a final fix for the vulnerability, or just a way to address the risk quickly, the fact that the user input makes it into the output as-is and may be executed under certain circumstances, should at least be considered a code smell and have a plan to fix it.

Post Scriptum

It’s probably also worth discussing why exactly I replace the text/html value in the Content-Type header with text/plain.

That’s an excellent topic for writing a separate article, but here are a couple of bullet points.

It all depends on how the endpoint is intended to be used.

-

If we intended to return a rich HTML output for our user, we wouldn’t construct the output manually in the code. We’d use templates and front-end frameworks for that. This is usually the recommendation from the Application Security team in the Cross-Site Scripting scenario discussed here. Together with the quick fix using plaintext as we discussed.

-

If we intended to return data in a REST API endpoint, we’d use JSON (or gRPC).

-

Looking at this existing code, it just wants to show a simple string on the screen. We recommend making it plaintext to eliminate the vulnerability as soon as possible using as little resources and time as possible.

The last time I saw an OWASP document recommending input validation instead was an "OWASP Secure Coding Practices Quick Reference Guide" that was not updated since 2010.